Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953 marked the beginning of a new direction for Soviet painting and the emergence of a new style known today as the ‘Severe Style’ or the ‘Severe School.’ Nikita Khrushchev came to power and delivered his so-called ‘Secret Speech,’ in which he denounced Stalin’s cult of personality and the brutality of his reign. This instigated the period now known as the ‘thaw’ that allowed increased freedoms in many areas of Soviet life including artistic production.

The initial artistic movement in the Soviet period had been the Avant Garde led by artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko and Mikhail Larionov and this incorporated neo-primitivsim, futurism, suprematism and constructivism. However by the 1930’s this movement was attacked as soulless and arid, and mocked for its cult of the machine. There was a reaction against the materialistic, utilitarian and pragmatic approach of the Avant Garde to culture that resulted in the party designing the template for Socialist Realism which remained in force as the approved style in Russia for nearly 60 years.

Socialist Realism became a formal state policy when Soviet Leader Joseph Stalin published the decree, “On the Reconstruction of Literary and Art Organisations” in 1932 which brought the history of the Avant Garde post-revolutionary period to an abrupt halt. The new style had to be simple (prost), comprehensible (poniaten), was to be maximally readable and to have the widest effect on Soviet citizens. Artists were encouraged towards “heroization” and to produce works that glorified the Soviet State and its heroes: – physicians, astronauts, scientists, workers and civil engineers. Aesthetic value and political value were closely linked and the style was required to be simple, iconic and disciplined.

In the early 1950’s and after Stalin’s death and the ‘thaw,’ exhibitions of Western art came to Russia for the first time including shows of international contemporary art, Picasso and Abstract Expressionism. Pioneering artists such as Nikolai Andronov, Geli Korzhev, Viktor Popkov, Pavel Nikonov, Pyotr Ossovski, Victor Ivanov and Tair Salahov rejected the happy cheerful subject matter of Socialist Realism, drew upon Soviet art of the 1920’s for inspiration and created the ‘Severe Style.’ They abandoned the polished classical style that was fashionable at the time and practised by artists such as Aleksandr Laktianov and presented a subject matter that they felt better reflected the grim austerity of post war Russia. Monumental paintings by Korzhev, Popkov and Salahov used subjects drawn from daily life with simplified form, colour and a dramatic cinematic manner.

Often these new works attracted significant opposition from those in power and Salahov remembers the times in an interview, “The Russian Soviet encyclopedia identifies me as one of the artists who started this movement along with Victor Ivanov and Pavel Nikonov. We set the course that many artists later followed throughout the Soviet republics. Of course, it was dangerous to chart such a course at that time. But I followed my heart. I did what my heart told me to do. We were severely criticized. They tried to stop us. They wouldn’t allow us to go abroad. They publicly criticized our works. Sometimes on the day just prior to the opening of a major exhibition, officials would come and demand that certain works be taken down. The excuse was that they simply did not fit into the broader scheme of Socialist Realism.

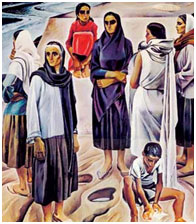

Again, look at my painting of the Women of Absheron. It provides another example of Severe Style. These women are waiting for their men to return from Oil Rocks. They’re worried. The families of those workers, their wives and children, were always waiting and anticipating the return of their men. They were always anxious about them because the sea can be dangerous. Suddenly tornadoes can whip up out of nowhere. So, they were always worried for their fathers, husbands and brothers. Their work was very difficult.”

Tair Salahov’s ‘Women of Absheron,’ oil on canvas, 1969.

Salahov continues, “I’ll never forget the time when one of the oil rigs collapsed and some of the workers died in the accident. Among the casualties was one of the pioneers who had been among those who first extracted oil at Oil Rocks. His name was Koverechkin. He and several of his friends died in that accident. This painting here in dark blue depicting the helicopter hovering above the pier commemorates that situation. That’s not Socialist Realism; that’s Severe Art. Few dared to paint like that. But my father had already been executed. So what else was there to be afraid of? I never asked permission to paint anything. I just did whatever came to mind. Sometimes there were people who would criticize me publicly while privately they would tell me that they liked my works. For example, there was Sergey Gerasimov, the First Secretary of the Soviet Artists’ Union. He was a distinguished artist himself. At the time, they were criticizing my painting of an oil worker with the red cigarette in his mouth. They were criticizing it at forums on the floor at assemblies. They were saying that it was very pessimistic and had employed such dark, unappealing colors. And the pessimistic expression on the man’s face, they said, looked like he was posing some question. Certainly, it wasn’t a good candidate for Socialist Realism. But after that session, some artists from Azerbaijan and people from our Ministry of Culture, including the minister himself, were standing around together and Sergey Gerasimov came over to me and said, “Tahir, they were criticizing you up there, but I have given it some thought. There was nothing in that painting that merited those comments.” And he shook my hand in front of all those people. It calmed me and eased my burden after so many attacks. He told me everything was fine and to continue my work. In that work, I was simply trying to show that man as I saw him and to reveal the truth that I knew about him. This painting is of a specific person-a man that I knew there. He didn’t pop out of my imagination. I knew that person. You can see how tired he is-exhausted from labor. That’s what they identified as Severe Style, but we were convinced that it was simply the truth.”

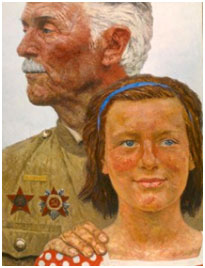

Korzhev’s ‘Anxiety’ is another key work of the movement. A critic described the work as reflecting, “a conscious lack of desire to find in nature transparent tones, beautiful shades, decorative combinations.” A father’s nightmares of WWII are contrasted with a daughter’s hesitant dreams of the future.

Geli Korzhev ‘Anxiety,’ 1965 – 1969, oil on canvas, 79 x 59ins.

These pioneering artists departed from the Socialist Realist dogma, its optimism, its structure, its ceremoniousness and its expression of Soviet Utopia. The thaw was a very exciting period for the Soviet people and it coincided with a talented group of artists who emerged in the 1950’s and continued through the 1960’s. Some artists, such as Korzhev and Ivanov maintained this style for many years and created a powerful body of work that was ignored until recently. Now the ‘Severe Style’ art is coming to be seen as the most important movement of post war Soviet artistic production.

The leading cheerleader for this art who coined the expression, ‘Severe Style,’ retrospectively in 1969, was the art critic, Alexander Kamenski. In 1961 he wrote that these artists had an “organic aversion to any kind of pose, bombast, falsity, to stock illustrations of a ready-made subject.” He also described these artists as “furious, passionate commentators on society.” In Russian “Severe Style” is “Surovyi stil.” “Surovyi” is often translated as “severe” but it can also be translated as rigorous, bleak, or austere.

‘Severe Style’ paintings are characterized by: – a sense of unvarnished truthfulness, grittiness, aloofness, formal qualities and devices. The paintings are often on a large scale—‘Anxiety’ is 79 x 59 in. (or about 7 x 5 feet), which led to the ‘Severe Style’s’ alternative name of Monumentalism.

The style utilized a simple palette of muddied greys browns and earth tones. The artists travelled around Russia drawing their subject matter from the reality they encountered. The 1930’s artists such as Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Alexander Deinika and Yuri Pimenov were admired as was Italian Neo-Realist cinema. Aleksandr Laktianov’s polished perfection as seen in such paintings as ‘Letter from the front’ was replaced with broad brush strokes and a sketchy rough quality.

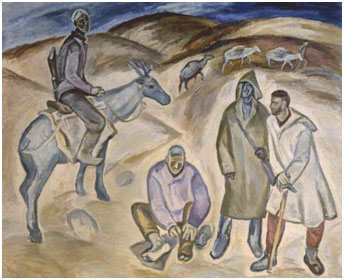

Other famous paintings of this school are Pavel Nikonov’s ‘Geologists’ of 1962 and Viktor Popkov’s ‘Memories, Widows’ of 1962.

Pavel Nikonov, ‘Geologists,’ 1969, oil on canvas, 182 x 225cm.

The Tretyakov Gallery in Krymski Val now has two rooms dedicated to this period where masterpieces by Popkov, Korzhev, Nikonov and Ivanov can be seen.

Viktor Popkov, ‘Memories, Widows,’ 1962, oil on canvas, 160 x 234cm.

Victor Ivanov, ‘Funeral,’ 1971, oil on canvas, 153 x 218cm.

With their choice of subject matter similar to the Wanderers, and with the passage of time, the ‘Severe Style’ can be seen as a movement indicative of its day but also firmly within the traditions of Russian art.

33,886 total views, 3 views today

Lindsay Russian Art - Agents and Dealers in Russian Art

Lindsay Russian Art - Agents and Dealers in Russian Art