Leonardo’s troubled Salvator Mundi hits the block

Oct 27th, 2017 | By Ivan Lindsay | Category: JournalJust when you thought this story couldn’t get any stranger ‘Leonardo’s’ Salvator Mundi has been consigned to Christie’s by Dmitri Rybolovlev and his Trusts and hits the block as a ‘special lot’ in a Post – War and Contemporary Art Evening sale in New York on 15th November. Yes, that’s a Contemporary Art Sale.

Unless you have been living on a deserted atoll for the last couple of years you will know that this painting is the one that triggered the Bouvier/Rybolovlev affair and is at the heart of various lawsuits involving the previous owners (a consortium of US-based dealers), Sotheby’s, Yves Bouvier and Rybolovlev.

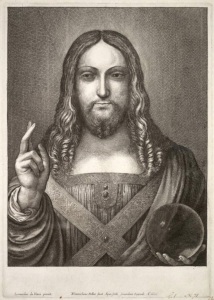

Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi

I have written several blogs about this murky story already so, very briefly, Bouvier sold around 37 paintings (including the Leonardo) to Rybolovlev for US$2bn. Rybolovlev maintains Bouvier overcharged him by US$1bn when he was supposed to have been on a 2% commission (around US$40m). The approximate US$960m discrepancy is the subject of a massive multi – jurisdictional court case that has already claimed the careers of various high-ranking judicial figures in Monaco. Bouvier defends his position saying he was acting as a principal, and not on commission, so he could charge what he wanted. In April 2017 a Singaporean Court, which was about to start deliberating on the case, directed it back to Switzerland where it awaits trial.

Many will be wondering why Christie’s have put this Old Master painting into a Contemporary as opposed to an Old Master sale and why they are auctioning this tricky painting as opposed to selling it privately. I would imagine it is because the Old Master department wanted nothing to do with it and the only chance they have of floating this painting is by letting the Contemporary spin doctors voodoo it off alongside the other key picture of the sale, Andy Warhol’s 30ft long Last Supper which carries a US$50m estimate (as opposed to the $100m they have put on the ‘Leonardo).

But can they really find another freshly minted art newbie from the outer reaches of the civilized world who is actually going to go for this? That Bouvier found Rybolovlev for this picture was a near miracle, but he had paved the way with some very good real pictures including Modigliani Nudes, Picasso’s, Klimt’s and Gauguin’s for many years beforehand (which Rybolovlev has been unloading recently at auction at huge losses over what he paid). But can Christie’s find another similar client? Maybe they already have as reportedly they a guarantor for the painting who will buy it if it doesn’t go above a certain price.

Loic Gouzer, the Swiss whiz kid in charge of the sale at Christie’s says, “Despite being created approximately 500 years ago, the work of Leonardo is just as influential to the art that is being created today as it was in the 15th and 16th centuries. We felt that by offering this painting within the context of our post war and Contemporary Evening Sale is a testament to the enduring relevance of this picture.” Enduring relevance?

There are many reasons why traditional Old Master collectors and museums will most likely pass on this. It is worth briefly recounting the history of the painting….while trying to make sense of it. It is believed by many that Leonardo painted a version of this painting although the prototype could have been a work of one his students. The Leonardo original idea seems to be based on the amount of copies there are and a couple of Leonardo drawings in the Royal Collection which are loosely related to the painting (a raised arm and a drapery study) and might be preparatory works. In their publicity material Christie’s say the painting is recorded in the Collection of Charles 1st (1600 – 1649) in an inventory drawn up a year after his death. In itself this is odd, if this is the only mention of such an important painting in the King’s collection, when there is a mass of information about the other major pictures in his collection. It seems that Charles only had one real Leonardo, a depiction of John the Baptist, and like all the important paintings in his collection that picture is well documented where it came from and where it went. He had other Leonardo school works such as the painting attributed to Leonardo he was given by the Barberini family in 1635. He tried and failed to buy Leonardo’s work on other occasions such as in 1623 when Juan de Espinosa in Madrid declined to sell him the two books of Leonardo drawings now known as Codex Madrid I and II.

Leonardo’s St John the Baptist had been been part of an exchange between Charles and the Duc de Liancourt where Liancourt received a Holbein of Erasmus, and a Titian Madonna, for the Leonardo. After Charles’s death it passed, in lieu of a debt, to the Keeper of the Cabinet Room, Jan Van Belcamp, who died shortly afterwards. His estate sold it a French merchant called Oudancour (for pounds 140) who was buying on behalf of the dealer, Everard Jabach, who in turn was selling to Cardinal Mazarin. The painting then returned to France and is now in the Louvre. In his exhaustive study of ‘Charles 1st and His Art Collection, the Sale of the Late Kings Goods (Macmillan, 2006),’ Jerry Broton makes no mention of a Salvator Mundi by Leonardo ever being in the Kings Collection.

The Salvator Mundi picture was engraved by Wenceslaus Holler in 1650 when, according to Christie’s, it was among the late King’s pictures. Holler attributes it to Leonardo although the painting in the engraving looks more similar to a Luini now in the Chiesa di San Dominico Maggiori in Naples.

Salvator Mundi attributed to Bernadino Luini and now in the Chiesa di San Bernadino in Naples

Despite the fact that Hollar was not known for pictorial accuracy the image in the engraving doesn’t look much like the Christie’s painting coming up at auction. Christie’s say it was next sold by the Duke of Buckingham in 1763.

Wenceslaus Hollar’s engraving of 1650

The Christie’s painting may or may not be the same painting as the one engraved by Hollar. According to Christie’s the painting for sale is indeed the painting from the Royal Collection that was engraved by Hollar which, after disappearing for 150 years, reappeared in 1900 when it was acquired by Sir Francis Cook and displayed at Doughty House, Richmond. Cook, born in 1817, died in 1901.

The businessman and collector, Sir Francis Cook, taken from the 1913 catalogue of his famous collection

The definitive Catalogue of Cook’s paintings at Doughty House and elsewhere was published by Heinmann in 1913 with Tancred Boronius writing on the Italian Schools. Cook began collecting around 1860 at the same time as Lord Wantage, Robert Holford, and Sir Henry Layard. J. Pierpont Morgan and George Salting were a little later.

At the time of the 1913 Catalogue there were 476 paintings at Doughty House and good collections of glass, furniture, books and Oriental Objects. It was a fine collection with Boronius stating in his introduction, “The Giants of Art contribute to make the Gallery – Van Eyck, Durer, Rembrandt, Velasquez, Raphael, Titian, Rubens, Van Dyck, and Turner are all present.”

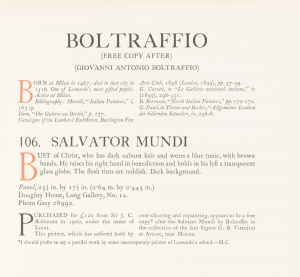

The Christie’s Salvator Mundi is listed as No 106 but not illustrated. It is attributed as a, “Free copy after Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio,” a Leonardo pupil. It is described as, “Bust of Christ, who has dark auburn hair and wears a blue tunis, with brown bands. He raises his right hand in benediction and holds in his left a transparent glass globe. The flesh tints are reddish. Dark Background.”

A late addition to the Cook Collection the catalogue states it was purchased in 1900 for pounds 120 from Sir J.C. Robinson (1824 – 1913), the collector, scholar and curator who built up the collection of the South Kensington Museum which later became the Victoria and Albert Museum. Robinson sold it to Cook as a work by Bernadino Luini but Tancred Bornius recatalogued stating, “This picture, which has suffered both by over cleaning and repainting, appears to be a free copy after the Salvator Mundi by Boltraffio in the collection of the late Signor G.B. Vittedini at Arcore, near Monza.” Herbert Cook, the grandson of Sir Francis Cook, adds in a postscript in the catalogue, “I should prefer to say a parallel work by some contemporary painter of Leonardo’s school.” Both Tancred Boronius and Sir J.C. Robinson were specialists in Italian Renaissance painting at a time when the subject was much better known than it is today and it clearly did not cross either of their minds that this painting was by Leonardo.

The Boltaffio Salavator Mundi entry from the 1913 Cook Collection Catalogue of the Italian School paintings complied by the Finnish art historian Tanced Boronius.

Christie’s continue by saying Cook’s descendants sold it at an auction in 1958 for around pounds 45. In 2oo5 it was bought by a consortium of US-based dealers including Alexander Parish, Robert Simon and Warren Adelson, reportedly for US$10,000 at an estate sale in the US, and they, having cleverly authenticated it to Leonardo, sold it via Sotheby’s to Yves Bouvier in 2013 for approximately US$80m who in turn sold it on to Dmitri Rybolovlev for a reported US$127m.

By the time the painting was bought by the US dealers the condition, already described by Boronius in 1913 as bad, had worsened. The walnut panel had split and was patched together with stucco and glue. ARTnews reported, “it was a wreck, dark and gloomy.” The dealers gave it to the New York based restorer Dianne Modestini who removed the overpaint and skillfully restored the painting back into Leonardo using the Hollar engraving and the Windor preparatory drawings as a template. Modestini took 6 years to Leonardo the painting into its current state of Leonardesque. And it is here that, perhaps allied to the amount of money that was being made and available for distribution, that reality seems to have evaporated and virtually everybody that came into the paintings orbit suspended their ability to look and started talking as if they were standing in front of the Mona Lisa herself.

On the left an old photograph believed to be of the Christie’s Salvator Mundi when in the Cook Collection and on the right post Modestini’s restoration.

It starts with Modestini herself. Quartz reported that “When the restoration was finally complete, Modestini says she fell into withdrawal, depression, and separation anxiety from seeing the painting move on. She likened the end of her restoration efforts to an emotional break-up: “It was a very intense picture and I felt a whole slipstream of artistry and genius and some sort of otherworldliness that I’ll never experience again.” When she realized the painting was by the master himself, “My hands were shaking, I went home and didn’t know if I was crazy.” Mmmm. Martin Kemp, the Leonardo scholar said, “He (Leonardo) draws you in but he doesn’t provide you with answers….it (the painting) has the uncanny strangeness that the later Leonardo paintings manifest.” Strange indeed.

According to Christie’s the list of scholars who are reportedly behind the painting’s new attribution includes Mina Gregori, Sir Nicholas Penny, Keith Christiansen, Carmen Bambach, David Ekserdjian and Everett Fahy. The general consensus was reached and a critical mass carried the majority along with them. One has to wonder whether these people have lost the ability to look and merely believe what they read or are told.

I first saw the painting in the exhibition ‘Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan’ at the National Gallery in 2011. It looked odd and out-of-place hanging next to masterpieces such as the Lady with the Ermine from the Czartoryski Museum in Cracow. Christ looks dopey and weird and much of what you see is clearly by a restorer. The real mystery is how it came to be included in this exhibition, which conveniently secured the painting’s attribution from a commercial point of view, and allowed the sale to Rybolovlev to follow shortly afterwards. Prior to the exhibition one of the then owners, Robert Simon, reportedly told Bloomberg: “I’ve assured the National Gallery that the painting isn’t on the market and there are no plans to sell it after the exhibition.”

We know there was probably, but not certainly, an original Leonardo, but when claiming a discovery is the lost original, there is always a risk that it is merely a good copy and the real original is either lost or may reappear on the future. At best this is a very damaged and heavily restored original. Alternatively it is a cleverly restored copy of an original or a work by a lesser master such as Luini or Boltraffio. The price alone should tell you there is a problem. A real Leonardo would be several hundred million US$, maybe $500 million. The $100m price is supposed to reflect a discount because of uncertain attribution and condition issues.

The painting is on a current world tour including New York, Hong Kong, San Francisco and London that is a high risk operation in itself for a 500-year-old painting on a wood panel which can split due to sudden temperature and humidity changes. It will be interesting to see Christie’s Contemporary art department can overcome the legal, condition, provenance and attribution issues and find a new home for this painting. Maybe the catalogue entry in the forthcoming sale catalogue will clear up some of the issues which, at the time of writing, seem less than clear. They are a very capable young team and masters of marketing in the new world of Social Media. We know they are experts of creating heat around the likes of Basquiat and Warhol and this is the first time their marketing expertise is being tested with an Old Master… and a difficult one. If successful then we will see more of this in the future. We shall find out on the 15th November.

There are many things “wrong” with the Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo. Most glaringly, the head of Christ is not proportioned correctly. Any student of artists’ anatomy will tell you that the eyes lie halfway between the top of the head and the chin. On ALL of the accepted Leonardo heads, this is the case. The Salvator Mundi does not follow this cannon of proportion. An image with such dubious anatomical proportion would not come from the hand of Leonardo.