Rybolovlev versus Bouvier case coming to trial in Singapore and dealers prepare to sue Sotheby’s over the “Leonardo” of ‘Salvator Mundi.’

Nov 30th, 2016 | By Ivan Lindsay | Category: JournalThe Rybolovlev versus Bouvier affair is shortly coming to trial in the Singapore International Commercial Court, a new court established in Singapore in January 2015 to settle commercial litigation involved in cross border disputes. Bouvier tried unsuccessfully to have the case heard in Switzerland but Singapore’s Senior Judge, Lai Siu Chiu, handed down a written decision in March that stated that, as Rybolovlev’s claims were not recognized under Swiss Law, holding the case in a Swiss Court would unfairly prejudice Rybolovlev’s case to Bouvier’s advantage.

The facts in this case have been thoroughly covered in this Blog and elsewhere so do not need repeating in detail again. Suffice to say Bouvier sold Rybolovlev 38 paintings for around US$2bn. On each painting he invoiced Rybolovlev with 2 invoices, one for the painting and one for a 2% commission. Rybolovlev now says this shows that Bouvier was working on an agreed 2% commission. Bouvier says the 2% was just for his expenses (US$40m of them) and he was not acting as agent for Rybolovlev but as a dealer selling paintings he owned to Rybolovlev and, as such, could charge whatever he liked. Rybolovlev maintains Bouvier took around US1bn fraudulently and unbeknown to him. It would appear to hang on whether Bouvier was an agent who owed certain responsibilities to Rybolovev or whether he was an owner who could charge what he wanted. There are lessons to be learned for any art dealer on what has happened here and anyone involved in the art trade would be well advised to follow developments. For a more detailed look at what actually happened see earlier posts http://www.russianartdealer.com/journal/buyers-remorse-monaco-rybolovlevbouvier-saga-continues/ and http://www.russianartdealer.com/journal/rybolovlev-bouvier-dispute-gathers-traction/

For those who are inclined to look at the case from a legal perspective the best assessment to date is in the legal decision summary of the Singapore Court of Appeal dated 21 August 2015 where Rybolovlev’s Mareva Injunctions (freezing Bouvier’s Assets) were lifted. The summary explores the complexity of the case and seems to conclude that Bouvier has a case to answer but evidence provided so far is not conclusive. For the full summary see http://www.singaporelaw.sg/sglaw/laws-of-singapore/case-law/free-law/court-of-appeal-judgments/18059-bouvier-yves-charles-edgar-and-another-v-accent-delight-international-ltd-and-another-and-another-appeal-2015-sgca-45

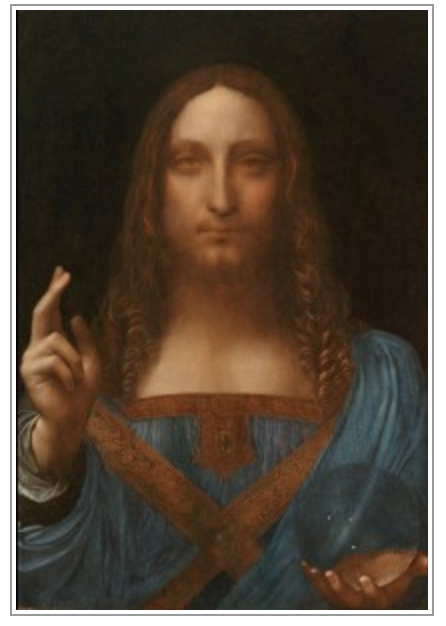

On the whole Bouvier sold terrific pictures to Rybolovlev and, if Rybolovlev were to sell, even so soon, he would surely make a considerable profit. However, at the end of Bouvier’s run, he made some lapses of judgement in his choice of pictures and Sotheby’s, who were involved in 12 of the deals, should also have known better. The most glaring of the mistakes was the so-called Leonardo of “Salvator Mundi.”

This painting, which is in bad condition, was apparently once owned by Charles I. It re-appeared in 1900 and was acquired by the English Collector, Francis Cook, one of the great collectors of his day. Cook’s descendants sold it at auction in 1958 for English pounds 45. Some years later it reappeared at auction where it was acquired by a consortium of dealers allegedly including the Old Master specialist Robert Simon. It was restored with the overpaint removed and amazingly placed in the exhibition, ‘Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan’ at the National Gallery London from 9th November to 5th February 2012. How the painting got into this show is a mystery as opinion on the full Leonardo attribution is divided. It is known there was a composition of this work by Leonardo, because there are existing copies of it, but Leonardo had a school of followers who painted in his style and there is always a danger with a painting like this that the original really is lost or that another better version may reappear in the future.

“Salvator Mundi,” a depiction of Christ, supposedly by Leonardo, sold through Sotheby’s to Bouvier in 2013 for US$80m who then sold it it a few days later to a Russian billionaire for a US$47.5m profit, according to Court Papers.

According to the New York Times the consortium of dealers who owned the painting prior to Rybolovlev acquired it at auction at an estate sale for under US10,000 around 8 years ago. The jump of pounds 45 in 1958 to US$10,000 circle 2008 to US$127m in 2013 is an enormous climb even amidst the staggering sums involved in this court case.

This picture, because many scholars do not agree on the attribution, and because what is visible is mainly painted by a clever restorer, is always going to be a problem from a commercial point of view and was always going to explode in Rybolovlev’s art collection. It was just a matter of when. With so many magnificent paintings available to a collector with Rybolovlev’s considerable ammunition, and eagerness to buy the best, this was a crazy painting for Bouvier and to sell him.

Now the situation has been further complicated by the consortium of dealers preparing to sue Sotheby’s for their role in selling the painting to Bouvier for US$80m who then sold it to Rybolovev for US$127.5m. Clearly US$10,000 to US$80m was not enough for this group and they are unhappy about the extra US$47.5m extracted from the picture by Bouvier and Sotheby’s role in this. Sotheby’s filed papers in a federal court in Manhattan last week in a pre-emptive move to block the suit they are expecting from the dealers. Sotheby’s says in the filing that it never knew Bouvier had the Russian billionaire waiting in the wings to pay much more for the work despite the fact they took the painting to Rybolovlevs apartment on Central Park where it was inspected by Bouvier and Rybolovlev. At the viewing at Rybolovlevs apartment, the Sotheby’s employee with the painting, Samuel Valette, said that he recognized the third man in the room as as someone having been associated with a previous sale to Mr Bouvier but according to the court papers, “It was not, however, until much later that Valette and Sotheby’s learned that this third man was Rybolovlev.”

The view over Central Park from Rybolovlev’s apartment. The property formerly belonged to the City Group CEO Sanford Weill.

Ryboloevlev bought the apartment in his daughter’s name, Ekaterina Rybolovleva, for US$88m in 2012 setting a record for the most expensive real estate transaction in New York. The price paid beat the previous record of US53m paid by J. Christopher Flowers in 2006 for the Harkness Mansion. One would have thought that the man in New York’s most expensive apartment, that was known to have been bought by Rybolovlev, examining a US$80m painting would have had a good chance of being Rybolovlev but, according to Sotheby’s, they were in the dark as to what was going on. Sotheby’s are also presumably required by their insurers to undertake due diligence on where and to whom they show US$80m paintings.

As everyone involved in this case runs for cover trying to protect themselves it is hard to know what really happened. However, a court in Singapore is about to have to decide on these very issues. What is for sure is that the whole business is damaging the art market and will force more transparency on all aspects of the art market. The banks are leading the way demanding more information on art deals than asked for by buyers and wanting full disclosure of all commissions being earned. They are also deciding what commissions they think are reasonable and refusing to process art deals if they think the commissions are too high. Art dealers are having to examine their transactions and try and tighten up their business practice. Depending on how this case goes art dealers are going to lean towards either being an agent or a principal. Often, as did Bouvier, they have a choice in a transaction. If they buy the painting first they are acting as a principal, as Bouvier is claiming here, or if they just take a commission they are an agent. But it very complicated and the laws of agency vary from country to country. For example, in England, some leading lawyers maintain, that even when acting as an agent, a dealer is a principal at the moment of the passage of title between the seller and the buyer. And the auction rooms, which were agents for hundreds of years are now building up their private sales departments where they sometimes act as principal. The Leonardo for example, was handled by the private sales department of Sotheby’s but were they acting as agent or principal? Anyway, without exploring that further here, we await the result of Singapore’s finest legal minds as the verdict and the law around the decision will have far reaching ramifications for international art dealing procedure.