Buyers remorse in Monaco – Rybolovlev/Bouvier saga continues

Dec 30th, 2015 | By Ivan Lindsay | Category: JournalThe Rybolovlev/Bouvier saga has now spilled over from the art press into mainstream publications such as the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. Town and Country Magazine have just published an interview with Dmitry Rybolovlev, a link to which is listed at the end of this article.

The details of the case are being revealed in court documents in Monaco, and have been widely published elsewhere, but in brief it appears that: –

Bouvier (according to Rybolovlev) was double dipping on commissions, i.e. taking a cut on both sides, while pretending otherwise (I know…..I was shocked as well). Rybolovlev says Bouvier was on a 2% commission and Bouvier indeed issued 2 invoices for each of the 37 pictures….one for the picture and one specifying a 2% commission. Bouvier now says his profit was his affair, as he owned the paintings, and his 2% commission invoice was for administrative expenses only (that’s US$40m worth of administrative expenses). Rybolovlev says he paid US$2bn for the paintings and Bouvier overcharged him US$1bn so, if true, Bouvier’s commission was actually closer to 50% than 2%.

Rybolovlev also says he thought that the intermediary between him and Bouvier, Tania Rappo, who was available day and night for a decade to offer encouragement to buy Bouvier’s pictures, was advising him as a friend, but she turned out to be on a 5% commission (a most disturbing discovery apparently for Rybolovlev, “We had a sincere friendship…. but the friendship was an illusion).”

Tania Rappo

The bank who handled the transactions, HSBC, have been drawn in to the case, initially alleging that Bouvier and Rappo had joint bank accounts (which facilitated the police arresting Bouvier) but later retracting this statement. Ms Rappo’s lawyer wrote, “It is impossible to exclude the possibility the (HSBC’S) false statement was made at the request of Mr Rybolovlev, who is further more one of the biggest customers of the bank.”

Rybolovlev’s attractive and steely eyed lawyer, the 31-year-old Tetiana Bersheda, realizes she has the case of a lifetime and is going for the jugular of all those lined up against Rybolovlev.

Bouvier’s main problem seems to have been that he is not an art dealer with experience of correct invoicing procedures and with knowledge of what pictures to avoid becoming involved in. He has a shipping company, which branched out into storage and Freeports. Thus he knew where some good art was stored and started selling it to Rybolovlev, a good idea but a also clear conflict of interest according to Larry Gagosian who said, “I’d consider it a terrible conflict of interest and would never keep art long-term in the warehouse of a dealer.”

If Bouvier had taken advice from an art dealer, or an art world lawyer, he would have been told to issue one invoice without specifying his commission or, if he needed to identify his commission, because that is what had been agreed with the client, to list the amount of his commission correctly.

Rappo fell into her role, apparently with no prior art world experience, having met Rybolovlev through her husband who was Rybolovlev’s dentist. She says she never discussed her commission with Rybolovlev because he “never asked.” She is probably right she had no legal obligation to do so but with a ten-year relationship and US$2bn of pictures sold it would probably have been prudent to get this out in the open. Rybolovlev said he would probably have forgiven Rappo if she had apologized to him and he wanted to hear her say, “I did it. I’m so sorry” but he says she denied everything when confronted.

Rybolovlev says that through his research he believes his money financed Rappo’s acquisition of several properties in Europe’s capital cities and Bouvier’s expansion of his Freeport business into Singapore and elsewhere. It seems that by the end Bouvier got greedy and became involved in selling some paintings to Rybolovlev that were guaranteed to cause serous problems such the 2 Picasso’s of Jacqueline Roque (Picasso’s second wife) which Roque’s daughter say belong to her and were stolen from a vault outside Paris which was supervised by a business partner of Bouvier’s. Rybolovlev has returned the US$30m Picasso’s to Roque’s daughter, Catherine Hutin – Blay, saying, “I feel solidarity with her, especially because there is a strong link between the portraits of her and her mother.”

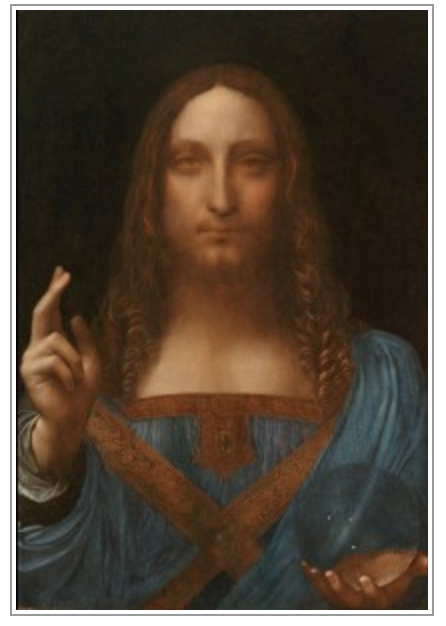

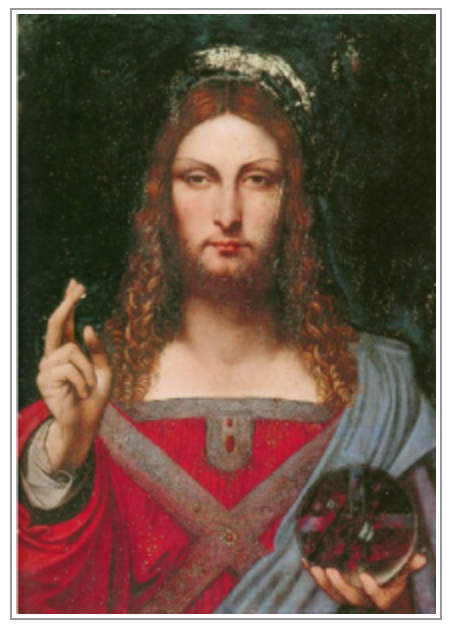

But the worst painting, which any art dealer would have told them to steer well clear of, was the so-called ‘Leonardo’ of ‘Salvator Mundi.’ This painting, which is in bad condition, was apparently once owned by Charles I. It re-appeared in 1900 and was acquired by the English Collector, Francis Cook. Cook’s descendants sold it at auction in 1958 for English pounds 45. Some years later it reappeared at auction where it was acquired by a consortium of dealers allegedly including the Old Master specialist Robert Simon. It was restored with the overpaint removed and amazingly placed in the exhibition, ‘Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan’ at the National Gallery London from 9th November to 5th February 2012. How the painting got into this show is a mystery as opinion on the full Leonardo attribution is divided. It is known there was a composition of this work by Leonardo, because there are existing copies of it, but Leonardo had a school of followers who painted in his style and there is always a danger with a painting like this that the original really is lost or that another better version may reappear in the future.

It seems that the consortium of dealers who owned the painting prior to Rybolovlev acquired it at auction at Sotheby’s New York, Friday 28th 1999, for US$332,500 against an estimate of 80,000 – 120,000.

Pounds 45 in 1958, US$332,500 in 1999, to US$127m in 2012 is an enormous climb even within the staggering sums involved in this court case. According to Rybolovlev, Bouvier made over US$50m on this picture alone.

This picture, because many scholars do not agree on the attribution, and because what is visible is mainly painted by a clever restorer, is always going to be a problem from a commercial point of view and was always going to explode in Rybolovlev’s art collection. It was just a matter of when and when seems to be now. With so many magnificent paintings available to a collector with Rybolovlev’s considerable ammunition, and eagerness to buy the best, this was a crazy painting for Bouvier and Rappo to sell him.

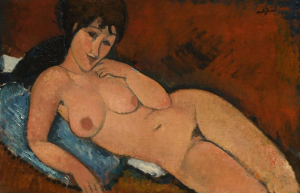

Having said that, in Bouvier’s defense, excluding the allegedly stolen Picasso’s and the dodgy ‘Leonardo’ Bouvier put together a magnificent collection for Rybolovlev, which Rybolovlev was brave enough to buy at huge prices, and if Rybolovlev waits for a few years, maybe even already, the collection will be worth many times what he paid for it. For example the recent acquisition of a Modigliani Nude by a Chinese billionaire for US$170m makes Rybololev’s four Modigliani nudes very valuable as Bouvier has been quick to point out saying, “Thanks to Yves Bouvier, Dmitry Rybolovlev possesses a set of four nudes (acquired for about US$200m)….today the conservative estimate for the nudes would be about US$500m.”

Many readers will by now be asking themselves “where is the story here….haven’t we seen this before and don’t they all deserve each other?” The various parties allege that we have a crooked art shipper, a confidante on the take, a bank up to no good, a young lawyer enjoying herself and a rich art collector full of buyer’s remorse having been schtupped for a billion. This is a story that has been played out many times in the art world although perhaps not as this level for a while. It is certainly a story familiar in human nature and we can find similar stories in Shakespeare, Chaucer and even in the Greek Tragedies.

The real story is in the considerable fallout caused by the case. Banks are running in the opposite direction anytime anyone mentions an art deal making it hard for art dealers to close deals. And the art market is not enjoying having the bad publicity and double-dealing aired in public which plays into the hands of those seeking more regulation in the art market.

It will be up to a Monaco Judge to decide what was the exact commission structure agreed on between Bouvier, Rappo and Rybolovlev. Rybolovlev appears to have done less due diligence that anyone in the history of art collecting. Had he ever sought a second opinion he would have been told that art dealers do not even get out of bed for 2% and alarm bells should have been ringing. Even one of the judges in the case has queried the believability of Bouvier operating on 2% saying, “It is at least doubtful, even if not wholly incredible, that the respondents genuinely believed that the remuneration for Mr Bouvier’s services was limited to the 2 percent fee that the respondents plainly knew they were paying him.”

Instead of seeking any independent council Rybolovlev apparently relied on his dentist’s wife for advice while buying a US$2bn art collection from an art shipper and the predictable result is that it has ended in tears. In Russia they say, Trust but Verify but Rybolovlev appears not to have done any verification. Should they agree to settle the art world would let out a collective sigh of relief but it appears both parties are digging in for the long haul and an extended public battle.

For Town and Country’s interview with Dmitry Rybolovlev see http://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/money-and-power/a4327/billionaire-defrauded-art-world-scheme/