Framing of Old Master paintings by Paul Mitchell

Feb 3rd, 2010 | By Ivan Lindsay | Category: EssaysIntroduction

In contemplating an Old Master painting, the frame is generally taken for granted. It is a fait accompli, and most of us may be unaware of how powerfully the frame can influence our perception and enjoyment of the picture within. The marriage of the two may be harmonious or discordant, enhancing or depressing, or somewhere in between. Most private and public collections contain pictures the true impact of which has been compromised by their frames – often in an insidious way – for decades or even centuries. But would we necessarily recognize the problem for what it is – or its extent?

The effect of the presentation can only beproperly assessed firstly by evaluating the current frame, and secondly by seeing the picture in alternative settings. Assuming that the owner of the picture may be suspicious of the ‘performance’ of a given frame, both steps might seem daunting. The first involves a knowledge of the history of frames; the second a situation in which appropriate alternatives may be shown. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate thepracticalities of the various issues and to indicate how framing problems may be solved, through a discussion of the means available, thepresentation of a brief history of framing, and the examination of some specific examples of reframing.

Frame Research and Photographic Archive

As a student of architecture and art history for six years in the 1960s, the author recognized the vast imbalance between the history of art and the history of frames. In both books on art and exhibition catalogues the frame was cropped from nearly every picture, and the literature on frames themselves was virtually non-existent. The frame was trapped in a no man’s land between the fine and decorative arts – and yet it so patently belongs to both.

In order to study the subject systematically the author started a photographic archive, recording pictures in what appeared to be original or contemporary frames in the main museums, galleries, private collections and major exhibitions throughout Europe, North America and Canada. By assembling this huge ‘jig-saw’it has been possible to identify the principal and subsidiary frame patterns which have evolved since the early Renaissance, recognize their characteristics and generally determine their originality – or otherwise – to their pictures.

These ongoing records, together with a study of architectural settings, furniture and related decorative arts, make it possible to identify and clarify the prevailing national and regional frame styles which were originally applied to a given artist’s work at a certain period. The results of this exhaustive study, made in collaboration with the frame historian Lynn Roberts, were published in 1996 as The History of European Picture Frames (a re-print of ‘The Frame’ article written for the Macmillan Dictionary of Art) and FRAMEWORKS: Form, Function and Ornament in European Portrait Frames. The latter accompanied the first ever exhibition of frames held by a public gallery in Britain, The Art of the Picture Frame at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Research into the history of frames has thus taken a great leap forward from previous landmarks (see bibliography), established by, for instance, Claus Grimm’s survey in 1978, The Book of Picture Frames, and by six successive exhibitions over two decades: at the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 1976; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1984; Art Institute of Chicago, 1986; Musée d’Orsay, Paris, 1989; Metropolitan Museum, New York, 1990; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam/Kunstforum, Vienna, 1995.

Frame history is today a specialized discipline and its application is essential in assessing the historically authentic reframing of Old Masters. At this point we may ask, ‘Why does an Old Master need reframing? How do we know whether its frame is the original or not? If not, why and when was it changed?’ To resolve these questions we need to gain an understanding of the origins, functions and evolution of the frame. [See next chapter….]

A Brief History of The Frame Origins

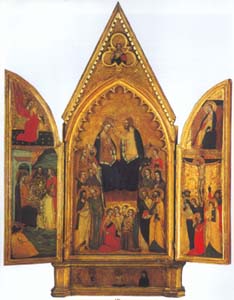

Frames evolved from the borders which appeared 3-4,000 years ago on vase and tomb paintings, and later on mosaics, enclosing narrative scenes and decorative panels. Early Christian art adapted these to the carved edgings of ivory book covers and diptychs, and finally of altarpieces. By this time the function of the frame had changed: not merely a decorative boundary, it protected and emphasized the work it held, and might have a strongly symbolic aspect. The gold and gems of early altar frames suggested the glories of Heaven; and the elaborate altarpieces developed in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italy imitated a mediaeval cathedral in cross-section, the ‘nave’, ‘aisles’, ‘crypt’ and so on each holding a painted fraction of the whole work.

These ecclesiastical settings were the first real picture frames. They were followed in the early Renaissance by court frames commissioned by monarchs and the nobility for purposes of status and propaganda. Such frames indicated power and wealth by the magnificence of their workmanship and often, too, by symbolic motifs. Secular frames followed: everyday versions of court frames, produced in increasing quantities from the fourteenth-century to the present, and in all degrees of cost or elaboration.

These types and their evolution may be classified by nationality: each country developing characteristic forms, of which the most successful might influence those of other countries – the Italian Renaissance cassetta frame, the eighteenth-century French Rococo frame (see A History of the European Frame, a study by nationality). They may also be divided across national boundaries by style: Renaissance, Mannerist, the polished wooden cabinetmaker’s frame, Baroque, Palladian and Rococo, the Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’, Neoclassical frames, and the academic or artists’ frames of the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries (see FRAMEWORKS. These two books interlock with and complement each other, creating a panorama of European framing history).

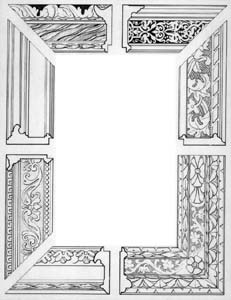

The Renaissance Cassetta

Various decorative techniques

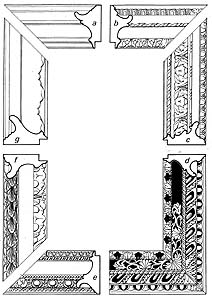

Both nationality and stylistic trends affected the main features of the frame: its overall form, ornamentation and finish. The salient frame of Renaissance Italy was the boxlike cassetta frame, finished with gold, paint or left in the wood. The central frieze might be adorned with foliate or geometric patterns (carved, moulded in stucco, painted, or decorated in sgraffito, where the design was etched through a layer of paint to the gold beneath), or it might be left plain, according to the purse and intention of the purchaser. The essence of these frames is the combination of linear outline and refined ornament, which echo and enhance the paintings of the period. [see next chapter….]

This diagram is reproduced as Fig.9 in A History of European Picture Frames by Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts.

Mannerist Frames

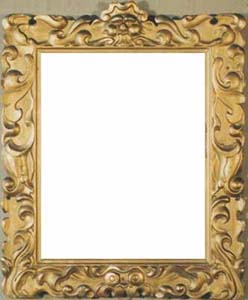

Mannerist frames developed in the Netherlands, Britain, Italy and Spain, between the mid-sixteenth – and the late seventeenth-century. They employed exaggerated organic or Classical architectural forms to create dynamic, sophisticated settings; like the Renaissance cassetta, they reflected the architectural interiors and decorative arts of the time. As the cassetta had mirrored the refined, organized interior of the Italian court, Northern Mannerist frames were influenced by contemporary interests in grotesquerie and in anatomical discoveries; Spanish Mannerist designs echoed extravagantly ornamented sculptural and architectural features, and Italian frames appeared in both forms.

The characteristic organic motifs which appear on many Mannerist frames (such as the one illustrated above) seem to have been generated by craftsmen – especially silversmiths – working in the courts of Bohemia. The melting cartilaginous shapes mimic the fluidity of metalwork, and caused this style to be known as ‘Auricular’ (like ear lobes). Examples were produced in Britain – the ‘Sunderland’, in the Netherlands – the ‘Lutma’, and in Italy – the ‘Medici’ frame. [See next chapter…]

The Cabinetmaker’s Frame

‘… an Ebony frame can enrich a poor canvas,

And make it look or sell as well as a good one.’

Constantijn Huygens, patron of Rembrandt.

The cabinetmaker’s frame, of stained or polished wood, was related both to the simplest cassetta frame and to architectural panelling and furniture. In Britain, the simpler forms of black and gilt ‘entablature’ frame were used, effective against backgrounds of tapestry, tooled leather or panelling, and when hung in groups. In seventeenth-century Holland the same frame type evolved luxury forms through the use of tortoiseshell, ebony and other costly woods from the Dutch colonies; ebony was particularly popular, complementing portraits of the mercantile classes in their severe black and white costumes, and highlighting landscapes against the pale, well-lit interiors of the Netherlands.

In Germany, Austria, Italy and Spain these wooden frames took more ornate forms, the veneer being worked into complex patterns of ripple, wave and basketwork mouldings. Such patterns took the place of gold leaf, refracting light from their faceted, polished black surfaces onto the painting. Frames like these are related to contemporary cabinets: Flemish examples of ebony and tortoiseshell, painted and inlaid, or German cabinets decorated with ivory and silver-gilt. [See next chapter…]

Baroque Frames

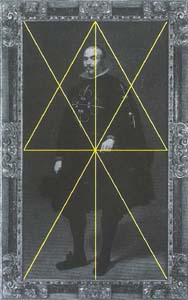

Baroque and Rococo frames reverted to gilding, except in Spain which used polchromy. Their dynamic came from the ‘cartouches’ of curling leaves, shells and volutes carved in the corners and often the centres of each rail. The imaginary lines drawn by the eye between these points were utilized by contemporary artists to emphasize compositional lines in their paintings, as shown here. The drama and opulence achieved by Baroque frames reflected the grandeur of seventeenth-century princely life, and the theatrical spirituality of the Church: they were also features of practical importance, sinc contemporary paintings needed strong settings with powerful sculptural forms to project and emphasize them against the splendours of the Baroque interior. [See next chapter…]

Rococo Frames

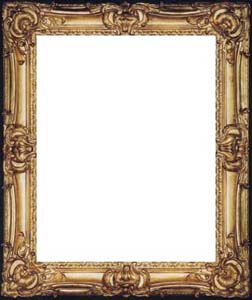

Rococo frames took a lighter, more delicate form: one of the apogees in the history of the frame, they became showcases for the skills of a battery of craftsmen – the master carver or menuisier, the répareur who recut fine details after the frame had been coated in gesso, and the gilder, who worked in different shades of gold, and in matt or burnished finishes. The court of Louis XV saw the creation of extravagantly sculpted grande luxe frames, often costing as much as the painting. Italy, Britain, Scandinavia and Middle Europe were inspired to create their own Rococo fantasies, woven in airily sweeping curves which could bear the carved and gilded trophies of monarchs, military leaders, artists, children, society beauties or bishops.

The Palladian Frame

Palladian and Roman frames provided a masculine, architectural alternative to Baroque and Rococo curves – particularly in Britain, where there were few, if any, complete Rococo interiors, and the taste for classical forms had never been entirely superseded. The British Palladian or ‘Kent’ frame, with its distinctive outset corners, is called after the architect and designer William Kent; he derived it from the late Mannerist work of Michelangelo, interpreted by Palladio and Inigo Jones. Kent, however, used it as part of a coherent interior, where for the first time architecture, fittings and furniture were designed as a single whole. The painting and its frame were completely integrated with the overall setting. The ‘Kent’ frame was decorated with strong classical mouldings, such as egg-&-dart, ribbon-&-stave and Greek fret, which suited its bold silhouette; it might be softened, however, by festoons or pendant drops of leaves and flowers, and elaborate trophy versions were also produced.

The Salvator Rosa Frame

The Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame was another linear style, current in Italy from the late seventeenth-century, introduced to eighteenth-century Britain by collectors who had made the Grand Tour, and still popular today. Unlike the flattened cross-sections of cassetta and Palladian frames, however, it had a sculptural, Baroque profile of alternating hollow and convex mouldings. These could be plain or progressively enriched with carved architectural ornament. The plainer forms were often used to frame the contents of an entire gallery, whilst the enriched versions, with up to five runs of decoration, created an opulent setting for the jewels of a collection. The British variants, known as ‘Carlo Maratta’ frames, were only produced in enriched or semi-enriched versions. Both types were named after the artists on whose work they were most often found.

Neoclassical and Empire Frames

Both the Palladian and ‘Salvator Rosa’ styles fed the Neoclassical designs of the late eighteenth- century. These were also stimulated by reaction against the excesses of the Rococo, and by an upsurge of interest in classical excavations and the study of the antique. The earliest Neoclassical furniture designs were French; they appeared in the 1750s, in the weighty, sober style known as ‘goût grec‘, and were followed by frames which used Classical ornament in the same bold idiom.

The style diffused outwards from France as Napoleon’s Empire spread over Europe, and led to the first truly international styles of the nineteenth-century, with their plain ogee, rounded or hollow profiles, and simple ornaments of moulded composition. These were also the first mass-produced frames, composition allowing labour-intensive carving to be replaced by moulded ornament. The frame – an object of art in its own right until the early nineteenth-century – became degraded into a badly made, banal setting for popular art, arbitrarily decorated and finished in cheap metallic leaf or gold paint.

Where collectors and patrons in the past had put their mark on their own collections by reframing them in the best taste of their own day, the newly rich art buyers of the nineteenth- century now used revivals of historical styles, reproduced in composition and schlagmetall (‘Dutch leaf’), because they fitted in better with the revival ‘Louis’ styles of nineteenth-century furnishing. Both past patrons, who reframed for reasons of status and possession, and nineteenth-century collectors, whose wobbly aesthetics could not accommodate the drama of, for example, authentic Baroque frames, are responsible for the loss of so many original settings from Old Masters and for the need of new knowledge in this important area.

Antique Frame Collections

That frames are now recognized as works of art in themselves is demonstrated by the permanent displays of empty frames in Paris at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the Reeves Collection in the Museum of Fine Arts in Dallas.

Few paintings have withstood the ravages of time in their original frames. Generally, the older the picture, the greater the probability that it will have been separated from its intended frame, and the divorce rate is highest amongst the Old Masters. Countless frames have been needlessly discarded over the centuries, so that original examples are extremely scarce. In most cases they are statistically rarer than the pictures they once surrounded. This is particularly evident, say, with the Renaissance aedicular or tabernacle frames created for devotional works: when the latter were sold in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries, the naked paintings were sent on their way alone for ease of transport, whilst the frames, once empty, were not considered worth preserving. Similarly, other large canvases would have been stripped from frames and stretchers, and rolled-up for removal to be reframed by their new owners.

The scarcity of period frames today becomes ever greater and their value consequently higher as the guardians of public and private collections recognize the benefits of seeing their paintings in authentic settings. The majority of empty antique frames of quality are held in the stocks of a handful of specialist frame dealers in Europe and America. The present author’s collection, accumulated over two generations, comprises over 3,000 examples of European frames from the fifteenth- to the twentieth-centuries. The inventory of Italian, Spanish, French, English, Netherlandish and German frames is unique for its breadth, variety and quality.

In order to provide examples of all the given permutations of nationality, period and style the stock needs to be of this scale and, as such, represents a formidable resource of antique frames. When to this is added the carving and gilding of reproductions (referred to later), private, trade and institutional clients are provided with a fully comprehensive framing service.

Thus, having examined the needs of historical expertise and the availability of frames mentioned in the Introduction, we can see examples of how effectively both may be applied. [See next chapter…….]

Period Reframing: Problems and Solutions

The Queen of Spain

‘… a Frame is so much a part of the Picture, that almost invariably we a little

change the effect or colour of some part the moment we place it in the frame,

and the work as certainly is the better for it. The finest picture, seen without

an appropriate Frame, loses a great advantage; as on the other hand it sustains

material injury from a Frame injudiciously selected… The Frame is the clear

Decanter not the brush…’

Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1828

A  B

B

C  D

D

A picture may be seen in different frames either by the use of computer-generated montages, or by physically standing the painting in successive frames, or both. For museum and privately owned pictures which cannot be brought physically to the frames, colour montages provide an excellent means of both recording and assessing the visual effects of differing frames. The frames may be seen in London in conjunction with the montages or a full-size image of the picture, and/or subsequently sent to be tested on the painting in situ. Occasionally, full-size mounted and cut-out photographs of frames are sent for trial when it is impractical to ship the originals.

The success of this process has been demonstrated for countless pictures over several decades, a recent example being the reframing of a seventeenth-century Velasquez workshop portrait of Marianne of Austria, Queen of Spain (see figs A,B,C,D).

The frames proposed were first-class examples of contemporary prevailing patterns, any one of which may originally have been applicable, and this selection was supported by numerous photographic archive examples from public collections. The choice, as in so many cases, was governed by the aesthetic relationship to the painting of the form, ornament and finish of each individual frame, as well as by the need to complement the frame styles on the other Spanish pictures in the gallery where this painting would hang.

Frame A was selected. Since the antique frame was slightly smaller than the picture, rather than alter the original a hand-carved reproduction was made, and then water-gilded, aged and distressed to match the antique finish.

The framing proposals for this portrait could only reasonably be expected to be seventeenth-century Spanish frames. However, for Dutch artists of this period two very different frame styles were simultaneously in vogue. [see next chapter …]

A Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape

Contemporary collectors of paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch artists would generally have been offered two fundamentally different types of frame – a linear design of polished or veneered wood, or a carved and gilded French frame. Both styles are depicted in interior scenes by Vermeer, Maes, Metsu, Steen, de Hooch and others.

The choice depended then (as it still does) on the owner’s nationality and pocket, as well as his personal taste, the proposed location of the painting, the harmony between painting and frame, and the relationship of the frame to others nearby.

Pictures are more likely to be reframed when their owners change than at any other time. A painting may remain undisturbed for decades or even centuries until it reaches the art market, when cleaning and conservation are usually undertaken and the presentation is reassessed. The perpetually strong demand for Netherlandish art and its mobility, witnessed by lengthy provenances, have resulted in regular reframing. A good quality seventeenth- or eighteenth-century French or English frame retained on a Dutch painting may be regarded as a bonus. For many works, and especially those of modest value, dealers have generally tended to use low-cost reproductions of Dutch frames, because the greater expense of period frames in either style may be risky when the buyer’s preference cannot be predicted.

The purchaser of the painting, whether through a dealer or at auction, has the opportunity to make a definitive decision as to the frame, possibly in collaboration with the dealer, as illustrated here in the case of a fine Hobbema landscape.

Initially the three proposals were viewed as montages, and then again in situ. It was instructive to compare their respective aesthetic merits.

A  B

B

In the ebony frame with ripple mouldings (A), the colour scheme of the picture was intensified by the black surround; and the wave mouldings, reflecting the scale of detail in the picture, created a subtle and even flicker of light around the subject. The warm brown tones of the pearwood frame (B) modified this effect, being the complementary colour to the predominating greens of the landscape.

C

The sumptuously carved Louis XIV period French frame (C) conveyed a sense of instant opulence. The finely-sculpted foliage and flowers on a cross-hatched ground are in tune with the scale and content of the picture and indicate the relative luxury of the intended setting. This was the frame selected by the new owner of the painting, reaffirming the fact that the majority of seventeenth-century Dutch paintings purchased by English and French collectors were framed in the traditional giltwood frames of the collectors’ native countries, to match the existing framing styles of their collections – many of which may still be seen in museum and private collections today.

‘… the gilded frame, with its bristling halo of sharp-edged radiance,

inserts a ribbon of pure splendour between the painting and the real world.’

José Ortega y Gasset, 1943

[The two exceptionally rare antique Dutch frames have since been sold to the National Gallery, Washington, for landscapes by Aelbert Cuyp, and are proving extremely difficult to replace.] [See next chapter…]

King Charles I Re-Presented

Nineteenth-century European collectors tended to reframe their Old Masters in contemporary settings, which may have suited their purpose and the interiors where the paintings would hang, but are clearly anachronistic and out of context. Examples of reframing on a grand scale for purposes of propaganda include Napolean’s mass rehousing in French Empire frames of works in the Louvre, a practice followed by some private owners, as with the Lavallard Collection of seventeenth-century paintings now in the Musée de Picardie, Amiens.

The Van Dyck and studio portrait of Charles I, having long ago been separated from its original setting, had been fitted with a late nineteenth-century oil gilded oak moulding, which had all the appearance of a temporary travelling frame. Very few early seventeenth-century English frames have survived, and the owner was extremely fortunate to acquire this magnificent (and exactly fitting) example, with its laurel-leaf border and exuberantly carved openwork scrolling oak leaves.

The transformation, illustrated here, underlines how important the appropriate setting can be for a picture, especially for a state portrait. The monarch, now fully attired, where he was previously en déshabille, has received a substantial added value well beyond the sum of his parts.

Our estimation of the value of a work of art is affected by its overall appearance far more than we realize. As we know, with countless consumer goods from scent to soft drinks, desirability is influenced by packaging. So too, for works of art. This truism is continually being demonstrated as paintings at auction or with dealers remain unsold due to mismatched or abysmally banal frames; on being reframed and allowed to perform at their best, these relics leap from the shelf into the arms of eager purchasers, their value enhanced manyfold.

Old Master Frames on Modern Masters

Works by modern masters present some of the most challenging of framing problems. Avant-garde painting styles developed faster than contemporary types of frame, with the result that late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pictures often clashed with the mass-produced, brightly gilded historical-revival settings available at the time. It is also generally acknowledged that the aesthetic values of the artists concerned have too often been compromised by the commercial demands of later reframing.

Modern artists sought a return to basic principles, and in doing so compared themselves with the Old Masters, the diverse framing styles associated with whom often prove the most compatible and expressive for modern works. The classical proportions, abstracted sculptural ornament and muted patina of Renaissance and Baroque frames possess a timeless quality, not necessarily related to a specific period of interior decoration. Used imaginatively, such frames can provide harmonious and exhilarating solutions to modern framing problems.

Many French Impressionist and Post Impressionist works have been reframed by dealers and owners during the twentieth-century in period French frames. These often work well, but they can dominate the subject and lack individuality. The advantage of a very extensive stock of Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical Italian and Spanish frames is fully appreciated by clients who are effectively able to see their pictures in a new light in these settings. By experimenting with such frames, many highly successful and enduring marriages have been made, notably with works by Monet, Degas, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Picasso. The winning combination is as recognizable as love at first sight, and its suitability as self-evident.

A striking example of rethinking the period French frame cliché is demonstrated by Matisse’s White Plumes in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Ornament on the previous frame was fussy and superfluous, and the excessive area of gold diluted the red background. In contrast, the seventeenth-century Florentine black and gold portrait frame looked as ‘modern’ as if designed by Matisse. The stylized corner and centre leaf ornaments, scale and finish harmonize with the forms and palette of the image. The painting can now be easily ‘read’, the frame has an integrity of its own, and together they make a highly impressive ensemble.

The Reproduction of Old Master Frames

The scarcity and value of antique frames are such that the demand for these settings must be satisfied to a large extent with reproductions. As with many products, these range from the tailor-made to the mass-produced, and inevitably often fail to do justice to the original model, frequently resulting in historically inaccurate pastiches.

Where availability, size, cost or all three forbid the use of antique frames, the ideal solution is to create as faithful a reproduction as possible. The factors necessary to this process are a wide-ranging choice of original models, plus the means of seeing them on the picture, an understanding of the materials and means by which they were originally made and finished, and skilled craftsmen who can imitate these techniques. A team has therefore been assembled of expert carvers, gilders and cabinet-makers who can achieve these criteria.

The selection of the model to be reproduced is also a prime responsibility, and the scope for this selection is increased from the available stock of antique frames through a wide range of references in the archive of photographic records. The choice may be aided by colour montages as discussed, and this combination of elements produces optimum results.

‘Thence to the frame-maker’s,

one Norris in Long-Acre –

who showed me several forms

of frames to choose by;

which was pretty, in little bits

of mouldings to choose by.’

Samuel Pepys, 1669

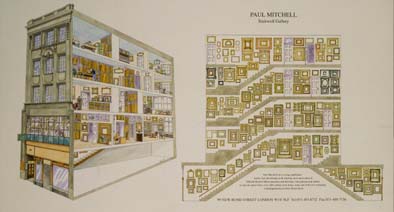

Paul Mitchell Ltd

Antique and Reproduction Frames

Conservation of Paintings

Address: 99 New Bond Street, London W1Y 9LF

Situated adjacent to Phillips Auctioneers,

between Brook Street and Blenheim Street

Tel: 020 7493 8732 Fax: 020 7409 7136

Email admin@paulmitchell.co.uk

Website www.paulmitchell.co.uk

Frameworks Exibition

Paul Mitchell Ltd is a long established family firm specializing in the framing and conservation of Old and Modern Master paintings and drawings. Our galleries and studios occupy the upper floors of an eighteenth-century town house, today one of the few workshop premises in New Bond Street.

Services

We offer a comprehensive antique and reproduction framing service to a broad spectrum of clients worldwide – museums, galleries, institutions, private and corporate collectors, international dealers and auctioneers. Expert consultation and research is provided on all aspects of the framing of Old and Modern Master paintings. Framing proposals may be viewed at our studios or by means of photomontages.

Period Frames for Drawings and Prints

Owners of Old and Modern Master drawings and prints are becoming increasingly sensitive to the quality of their display.

The diversity of styles in our extensive stock of period drawing frames bears witness to the importance attached by past collectors to the presentation of graphic works. Helped by the flexibility of mount sizes, the judicious selection of a frame is deeply satisfying. The status and individuality of the subject are enhanced and the frame may be enjoyed as a work of art in its own right.

Reproduction Frames

Availability or size may restrict the use of antique frames. In our workshops close to London we make frames to any specification, as well as altering and restoring antique frames. Our expert carvers, gilders and cabinet-makers create the highest quality replica frames of all periods and finishes, from the simplest to the most ornamental. The widest possible resource of models and patterns is provided by our current inventory, records of past stock and photographic archive.

Museum Clients

Other than private collectors, our museum and public collection clients include the following:

Amsterdam Historisches Museum

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Birmingham City Art Gallery

Berlin Picture Gallery

Bridgestone Museum, Tokyo

Castle Howard, Yorkshire

Art Institute of Chicago

Detroit Institute of Arts

Dulwich Picture Gallery

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Indianapolis Museum of Art

Kimbell Art Museum, Forth Worth

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum, New York

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

National Gallery of Ireland

National Gallery, London

National Museum of Wales

National Gallery of Art, Washington

National Gallery of Scotland

National Portrait Gallery, London

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

North Carolina Museum of Art

Philadelphia Museum of Art

San Diego Museum of Fine Art

Saint Louis Art Museum

Seattle Art Museum

Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Helsinki

Southampton Art Gallery

Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische

Galerie, Frankfurt

Taft Museum, Cincinnati

Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo

Virginia Museum of Fine Art

Waddesdon Manor, National Trust

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

York Art Gallery

Distinguished Pictures Re-Framed

Among the hundreds of Old Masters for which we have supplied period antique frames are the following:

Leonardo Ginevra de’Benci National Gallery, Washington

da Vinci

Raphael The Colonna Madonna Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

Fra The Holy Family with Saints Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Bartomoleo

Sebastiano Pope Clement VII Getty Museum, Los Angeles

del Piombo

Pontormo Cosimo I de’Medici Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Lotto Gian Giacomo Steur and his Philadelphia Museum of Art

Son, Gian Antonio

Mantegna St Mark Stadelsches Kunstinstitut

Frankfurt

Titian A Venetian Procurator Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

Tintoretto The Raising of Lazarus Minneapolis Institute of Art

Caravaggio St John the Baptist Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Kansas

Guercino Angels Mourning the Dead National Gallery, London

Christ

Brueghel St Paul’s Departure from North Carolina Museum of Art

Cesarea

Holbein Lady with a Squirrel National Gallery, London

Mabuse Henry III, Count of Kimbell Museum of Art

Nassau-Breda Fort Worth

Rubens Sacrifice of Abraham Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Kansas

Van Dyck Marchesa Elena Grimaldi National Gallery, Washington

Cuyp Landscape with Cattle National Gallery, Washington

Hobbema Wooded landscape with Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Watermill

Van Flowerpiece Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Huysum Kansas

Pieter Still Life Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Claesz Kansas

Melendez Still Life with Oranges National Gallery, London

Batoni Portrait of William Fermor Museum of Fine Arts, Houton

Ramsay Portrait of the Artist’s Niece The Huntington, California

Romney Portrait of Colonel Clitherow Detroit Institute of Arts

Stubbs Lord Grosvenor’s Arabian Kimbell Art Museum

with a Groom Fort Worth

Turner The Rape of Europa Taft Museum, Cincinnati

Millais The Random Shot Yale Center for British Art

New Haven

Delacroix Combat scene Art Institute of Chicago

Courbet Flowerpiece Norton Simon Museum

Pasadena

Degas The Milliner’s Shop Art Institute of Chicago

Monet Rouen Cathedral, West Facade National Gallery, Washington

Pissarro Boulevard de Clichy The Clark Art Institute

Williamstown

Renoir Seated Bather Detroit Institute of Arts

Matisse The Three Bathers Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Seurat Port-en-Besin Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Van Gogh White Roses National Gallery, Washington

Cezanne Madame Cezanne Detroit Institute of Arts

Modigliani Portrait of the Artist’s Wife Norton Simon Museum

Pasadena

Publications

The principal publications by Paul Mitchell Ltd, in association with Merrell Holberton Ltd, are:

FRAMEWORKS: Form, Function and Ornament in European Portrait Frames

Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts

ISBN 185894 037 0 480

480pp, 374 illustrations, 297 colour (1996)

‘….a huge and scholarly volume on European portrait frames … a highly thought provoking book that cannot fail to have a profound influence on art scholarship an museum practice.’

Antiques Trade Gazette

‘… pure delectation, avec des superbe illustrations…’

L’Art Plein Cadre

‘…cet imposant album retrace ainsi revolution stylistique d’un art decoratif…’

L’Objet d’Art

‘…a gorgeously illustrated study…[a] fascinating and well- researched book…’

Birmingham Post

FRAMEWORKS is the first full scale study of picture frames presented stylistically rather than by nationality. Lavishly illustrated, with nearly 300 colour plates, it reproduces major paintings with their frames from collections worldwide. Illustrations of contemporary interiors, furnishings and objets d’art set the frame in its context and reveal how styles evolved across national boundaries. The outstanding quality of the illustrations brings the craftsmanship of the carving and the gilding vividly to life. This is one of the most exciting visual adventures in art historical literature.

A History of European Picture Frames

Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts

ISBN 185894 036 2

136 pp, 48 mono illustrations, 5 line drawings (1996)

‘…massive and many-layered…’

Burlington Magazine

‘…one of the most comprehensive and informative books on the subject that I have come across….The line drawings are superb…’

Art Business Today

‘…a substantial scholarly text…[an] authoritative reference book…’

The Picture Restorer

‘…le complément indispensable de ce trés beau livre [FRAMEWORKS].’

L’Echo

This panoramic survey of frame styles, classified by nationality, represents the culmination of more than 20 years’ research and the creation of an immense photographic archive of information. First commissioned from the Macmillan Dictionary of Art, it has been republished independently in acknowledgement of its pioneering status. The diagrams of over 250 frames are drawn directly from works in their original or contemporary settings, creating a visual pattern book which is complemented by the wide historical range, factual depth and new research included.

FRAMEWORKS and A History… are companion works and may be purchased

– as a pair or individually – directly from Paul Mitchell Ltd.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Further Recommended Reading on the subject:

Antiche cornici italiane dal Cinquecento al Settecento

Exhib. cat. by M. Mosco

Tokyo, 1991; Florence, Galleria deigli Uffizi, 1991

The Art of the Edge: European Frames, 1300-1900

Exhib. cat. by Richard R. Brettell and Steven Starling

Chicago, Art Institute, 1986

The Art of the Picture Frame: Artists, Patrons and the Framing

of Portraits in Britain

Exhib. cat. by Jacob Simon

London, National Portrait Gallery, 1986

R. Baldi, G. Gualberto Lisini, C. Martelli and S. Martelli

La cornice fiorentina e senese: storia e tecniche di restauro

Florence (Alinea), 1992

Cadres des peintres

Exhib. cat. by I. Cahn

Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 1989 (37 figs.)

T. Clifford, ‘The Historical Approach to the Display of Paintings’

The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship

I, 1982

F. G. Conzen and G. Dietrich

Bilderrahmen. Stilverwendung Material

Munich, 1983

W. Ehlich

Bilderrahmen von der Antike bis zur Romantik

Dresden, 1979

S.E. Fuchs

Der Bilderrahmen

Recklinghausen, 1985 (146 illus.)

Claus Grimm

Alte Bilderrahmen. Epochen-Typen-Material

Munich (Georg Callwey), 1978 (survey with extended bibliography;

483 illus.)

Clauss Grimm

The Book of Picture Frames (with a supplement on ‘Frames in

America’ by George Szabo)

English edn. 1978, New York (Albaris Books) 1981

(survey with 30 figs. and 489 plates)

M. Guggenheim

Le cornice italiane dalla metà del secolo XV allo scorcio del XVI

Milan, 1897

Henry Heydenrijk

The Art and History of Frames

New York (Heinemann), 1963 (100 illus.)

In Perfect Harmony: Picture + Frame 1850-1920

Exhib. cat., ed. Eva Mendgen

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, 1995

Italian Renaissance Frames

Exhib. cat. by T. J. Newbery, G. Bisacca and L. Kanter

New York, Metropolitan Museum, 1990 (24 figs., 84 plates)

P. Mitchell, ‘The Framing Tradition’ in

Picture Framing, ed. Rosamund Wright-Smith

London (Orbis), 1980 (9 col. plates)

Paul Mitchell, ‘Italian Picture Frames 1500-1825: A Brief Survey’

The Journal of the Furniture History Society, xx, 1984

pp. 18-27 (30 plates)

Paul Mitchell, ‘A Signed Frame by Jean Chérin’

The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, IV

1985, pp.147-54 (8 figs.)

Paul Mitchell, ‘Frames’ in

Guide to the Exhibited Works in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

Caroline de Watteville, Lugano and Milan, 1989, pp. 365-71

Prijst de Lijst

Exhib. cat. by P. J. J. van Thiel and C. J. de Bruyn Kops

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, 1984

trans. as Framing in the Golden Age, 1995 (117 illus & diagrams)

Lynn Roberts

‘Nineteenth Century English Picture Frames I: The Pre-Raphaelites’

The International Journal of Museum Managaement and Curatorship, IV

1985 pp. 155-72 (24 illus.)

Lynn Roberts

‘Nineteenth Century English Picture Frames II: The Victorian High

Renaissance’

The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, V

1986 pp. 273-93 (25 illus.)

Lynn Roberts

‘Victorian Frames’ in

In Perfect Harmony, 1995, pp.57-86

F. Sabatelli, E. Colle and P. Zambrano

La cornice italiana dal Rinascimento al Neoclassico

Milan, 1992 (115 figs., 117 col. plates)

Alfred Strange and Leo Cremer

Alte Bilderrahmen

Darmstadt, 1958 (25 illus.)

H. Verougstraete-Marcq and R. van Schoute

Cadres et supports dans la peinture flamande aux 15e et 16e siècles

Heure-le-Romain, 1989

Revue de l’Art, no. 76, 1989

(an issue dedicated to articles on the frame)

Paul Mitchell and Lynn Roberts

‘Notes on Turner’s Picture Frames’

Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 17. no. 3

Sept. 1998, pp. 324-333

Dear mr. Mitchell,

From a distance in time and space I like to send you my greatings.

We have met in the Frans Hals over 30 years ago by appointment of mr. Pieter van Thiel.

I have enjoied your books.

Until this day I have succeeded to keep on working with pleasure in the beauyfufl craft of woodcarving.

I would like to invite you to browse my website.

Maarten Robert.

[…] Master Paintings” by Paul Mitchell and briefly summarizes the origin of framing on his post. (http://www.oldmasters.net/journal/framing-of-old-master-paintings/) Evolving from the carved borders on vases and tombs, framing developed into elaborate golden […]