Sotheby’s riding high for now… but looking vulnerable

May 21st, 2015 | By Ivan Lindsay | Category: JournalI have written elsewhere about Sotheby’s share price being a leading indicator for the general health of the art market and indeed for the stock market in general. See http://www.russianartdealer.com/journal/aggressive-activist-investors-shake-sothebys-spears-wms-magazine/

The following article written by James Stefurak for Seeking Alpha is an in-depth examination of Sotheby’s, its share price, and the general health of the art market.

- Sotheby’s exposed to the enormous art bubble.

- Stock price looks vulnerable.

- Shares should be avoided, sold or hedged.

An auctioneer and dealer of some of the finest art and collectibles in the world including diamonds, wine and watches, Sotheby’s (NYSE:BID) has been synonymous with class, privilege and status since 1744. This bastion of high-society has ridden an unprecedented wave of art market mania, driven not by anything resembling fundamental valuation by any stretch of the imagination, but rather a global credit and liquidity boom. The art market has been absolutely on fire over the last couple years with record-breaking prices for paintings. Further, Christie’s recently auctioned off $1 billion in art over just a 48-hour period. Yet despite an art market setting higher and higher records, Sotheby’s revenue growth actually declined almost 1% year over year.

It’s possible that Sotheby’s themselves sees the risk in the art market. In an apparent attempt to “diversify,” the company recently expanded into different areas including collectible cars and real estate services. Sotheby’s purchased a minority stake in RM Auctions in February 2015, rebranding it as RM Sotheby’s. This new venture went on to set a new record for a private auto collection (almost $54 million) just a couple weeks ago. Like Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A), Sotheby’s has basically been licensing its name and brand into the real estate market. Scroll through the TV guide and you can see classic car auctions and house flipping infomercials, 2.0. It’s not hard to see that these ancillary luxury industries are no doubt in their own bubbles as well – the key ingredient being cheap money. Given these considerations, Sotheby’s appears inherently exposed to all things luxury and has a poor risk-reward profile given the manic nature of so many different sectors they are involved in.

Let’s Start the Bidding

The catalysts for our cautionary Sotheby’s stance arise from two macro concerns:

1) Exit the Dragon- A major growth driver for art world is Asia, but a further rise of the U.S. dollar will strain these weak-currency, debt-laden nations. Sotheby’s has increased exposure to Asian art, mostly China, and that segment was up 31% year over year. Realistically, much of art’s value is correlated to the high-end art buyers themselves, so the performance of these nations’ economies and equity markets is crucial. The Hang Seng and Shanghai exchanges have been on a tear, exhibiting very sharp snap-back rallies but have they gone too far, too fast. More worrisome is as of mid-2014, China’s total debt has almost quadrupled since just 2007, rising from $7.4 trillion to $28.2 trillion, according to McKinsey. Much of this debt has been raised outside of Asia and is U.S. dollar-denominated (the same goes for the art since transactions are primarily in USD payment), so as the dollar rises, the debt becomes harder to pay back. This could price out new art buyers who simply won’t be able to afford the art anymore. It’s worth noting a headline appeared on CNBC right before Tuesday’s market close that ‘China May Raise Import Tax on E-Commerce.’ There is no way of knowing what this will encompass at this stage but since Sotheby’s is trying to focus more on internet sales, and Chinese art buyers, this could potentially be bad. Remember the old Chinese proverb, “no tree grows to the sky.”

2) DeflateGate- A rise in interest rates should have a negative impact on global capital markets (equity, real estate, fixed income/credit, etc.), the source of capital for art purchases. Also, the faster rates rise, the more abrupt the halt will be and greater the chance that credit freezes up. The rate rises could also foster a more worrisome development, deflation. Deflation, its definition and very existence hotly debated, is often dismissed by many as nonsense. Our favorite interpretation includes not only the supply of money in the economy, but also credit. Central banks have injected trillions globally since the financial crisis. It’s worth remembering there is over $200 trillion in worldwide debt and some estimate only about 2% is AAA rated (much of that AAA-rated debt is coming from countries with negative interest rates, so AAA ratings seem dubious). It seems logical to us that these two numbers have nowhere to go but down. If debt defaults begin in earnest, deflation could reappear and bring down all asset values. Monitor the U.S. 10-year Treasury yields and 3-month LIBOR for warning signs.

Vanity Fair

The media has been fixated on the art boom in recent years. Media exposure, in turn, brings out more art buyers and further feeds egos. Like advertising sponsorships, art buyers love to be associated with the “brands” of famous artworks they’re buying. Many probably welcome the absurdity of prices paid as a “see what I can afford” reaffirmation. Once art collecting is no longer en vogue and the absurdity of the prices becomes a negative again and not a positive, many art buyers will turn out to be art “renters” and be dumping their pieces, if they can.

The Shady Side

Art and collectibles have always been fervor for intrigue, whether its Faberge eggs in James Bond movies or grandiose heists in the ‘Oceans’ movies. Even off the silver screen, the art world has been a haven for money laundering and tax evasion. I’ve read accounts of drug dealers taking payment in artworks (easily transportable) and then selling it for cash where the money is now fresh from the laundromat. Even today, CNBC’s Robert Frank is reporting on a major scandal brewing involving two missing Picasso’s, an art dealer and a Russian billionaire. The paintings have changed hands apparently three times already in just a few years. More stories like this are sure to continue and will end up being the art market’s demise.

In 2014, the American Royalties Too Act was introduced to Congress which would impose a 5% resale fee with a $35,000 cap on sales of art in large auction houses, so the artist can receive royalties essentially in the event of an underpricing by the auction houses. Although the passing of the bill is a long-shot by all accounts it would affect Sotheby’s and House Representative Jerrold Nadler (D) New York introduced the bill and was quoted as saying “To me, the bill is a question of fundamental fairness.” Just choosing the word “fairness” draws a line in the sand and turns it into a populist issue. There are so many private transactions and works sold at ‘secret prices’ that you can be sure some politician will eventually succeed in shining a spotlight into these operations. There is a steady drumbeat of more regulation in countless industries and with the current vitriol against the wealth gap, which has arguably never been greater in history, you can be sure more regulation will eventually find the art money.

Art Wars

Sotheby’s operates in three main segments; Agency (commission based, acting “as agent”), Finance (makes credit available to various participants in the art procurement market), and Principal (essentially speculating on art themselves). Sotheby’s experiences very strong competition from its chief rival, Christie’s auction house, in all these sectors. There’s essentially a market duopoly between Sotheby’s and Christie’s, and while that might sound positive, it’s a double-edged sword. The competition between them has gotten fierce as art prices and associated media coverage have skyrocketed.

Christie’s already has one built-in advantage in gaining listings – they’re private. By being a private company, they are allowed to disclose less to the public in terms of fee information and private arrangements, etc. The competitive disadvantage has caused Sotheby’s to increase its risk profile in its agency segment to attract new art listings. In its Agency business, Sotheby’s essentially acts as a market maker. It offers ‘auction guarantees’ (a minimum guaranteed sale price, by Sotheby’s, for a piece of art listed at their auction). If the artwork or collectible sells for less than the guaranteed price at auction, Sotheby’s must fund the difference. If the piece doesn’t sell at all, Sotheby’s basically owns it. True, they can just use proceeds from another sale to cover it but the risk still remains. Obviously, the higher the guarantee, the more likely the seller will be to list with Sotheby’s. If Sotheby’s doesn’t step up with big guarantees, they’ll lose the commission to a competitor (probably Christie’s). Sotheby’s auction guarantees have aggressively increased and as of March 31, 2015, Sotheby’s had guarantees of $176,912,000. This is up from $123,300,000 as of December 31, 2014, representing an increase of 43% overone quarter! The guarantees are inherently a bet that the art bubble will continue to inflate, and Sotheby’s is dramatically ramping up as the art market inhabits bubble territory. In fact, it could be argued that the guarantees themselves are helping fuel the mania. Sotheby’s issues the following statement on auction guarantees in its latest 10-Q, “Auction guarantees create the risk of loss from the potential inaccurate valuation of art.” Is there such a thing as accurate valuation of art?

So while Sotheby’s may seem somewhat insulated to the art market bubble prices with 82% coming from seemingly less risky agency segment, (collecting commissions by facilitating transactions) it’s actually much more exposed than many believe. While the company’s Principal segment is supposed to be the speculative area, we see plenty of it, potentially, in agency.

There are some other trends from Sotheby’s financials that are worth a second look. While Sotheby’s auction commissions for the agency segment were up, their margins have been eroding for years now. From Sotheby’s 10-K:

And from the footnotes on page 12 of Sotheby’s latest 10-Q, Sotheby’s discloses accounts receivable of $134.2 million at the end of Q1 2015, up from $116 million in the prior quarter. The footnotes disclose “Sotheby’s is liable to the seller for the net sales proceeds whether or not the buyer makes payment.” There is certainly a lot of trust and confidence apparent in this segment, evident by Sotheby’s growing auction guarantees and these accounts receivable. When the next credit tightening cycle or art market slowdown hits, Sotheby’s will be forced to be conservative, whether on its own accord or by a breakdown in its financing chain. Therein produces a vicious cycle since reducing auction guarantees could stifle overall auction activity. When 82% of your revenue comes from agency, it’s worrisome.

Sotheby’s Financial Services

Sotheby’s finances the purchases of art to various art dealers as well as provides loans to various participants in the art markets. While only about 8% of Sotheby’s revenues, it is growing rapidly at 123% year over year. Sotheby’s gets backed by credit arrangements with “an international syndicate of lenders…” which include principally GE Capital (NYSE:GE). In an 8-K from August 2014, Sotheby’s disclosed an increase in its revolving credit commitments with GE Capital by over 41% to $850 million from $600 million for the agency and financing segments of Sotheby’s business. This is no doubt at least partly responsible for the growth in Sotheby’s Finance segment since then. Recall what happened to GE’s credit arm back in the financial crisis, which they shed post-crisis. Time will tell if this “new” GE Capital operates in a more prudent manner.

Additionally, Sotheby’s has $661,657 in term loans outstanding within its notes receivable section on page 12 of the latest 10-Q, which is up from $360,830 a year earlier, an increase of 83%. These are considered “secured” loans, but not secured by cash or real estate, but apparently by the art collection itself. In the footnotes, Sotheby’s vaguely explains these term loans as “general purpose term loans secured by property not presently intended for sale.” Sotheby’s mentioned they wanted to “leverage notes receivable” to lower their cost of capital (increase spreads on loans) but this seems a risky way to accomplish that goal. In 2014, Sotheby’s has identified growing the SFS portfolios size as an opportunity and this also is adding risk since the SFS actually borrows money from the ‘core’ auction business. Further, the loan-to-value, LTV, for Sotheby’s loan portfolio could also be significantly understated, especially in a credit tightening situation, since the LTV metrics are marked to the ‘low value estimate of the collateral.’ The revaluation of the loan collateral is done on an annual basis, unless there is a material circumstance occurs, and is done by ‘Sotheby’s specialists’ so there is certainly the opportunity for some positive bias associated with the ‘revaluations.’

Risks to Our Thesis

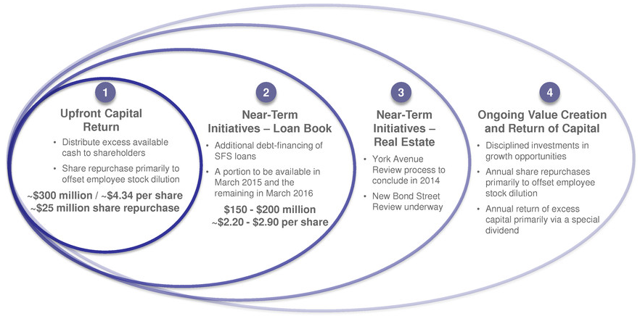

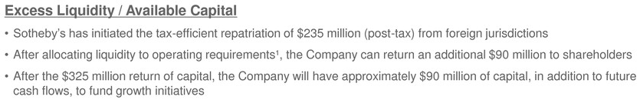

The main reservation associated with our cautious stance is Sotheby’s strong investor base. Its top shareholder is Third Point, LLC who is a very experienced hedge fund with a strong track record of creating value for shareholders, as has already been seen in the various payouts to shareholders. In an 8-K from January 29, 2014, Sotheby’s unveiled its ‘Capital Allocation and Financial Review’ where they list out the main points to their plan to add shareholder value going forward so there could be additional value created through a variety of new initiatives and strategies.

Another risk that can’t be ignored is that large shareholders may want to take Sotheby’s private to better compete with Christie’s and the like. Disclosed in filings that became public through lawsuits Third Point brought against management, there have been questions asked in meetings between the parties regarding operating as a private company. Sotheby’s second largest shareholder, Marcato Capital management is no stranger to deals either. Marcato was an activist investor and large shareholder of LifeTime fitness and urged the health club operator to execute a REIT conversion, which it subsequently did. The stock went up considerably on the news, and recently it’s been announced that a private equity team is buying out LifeTime (taking it private) resulting in a large gain for Marcato. The more barbarians appear at the gate, the more likely something could happen.

From the January 2014 Sotheby’s 8-K Current Report,

This is a strong plan, but it seems the majority of the gains have already been realized. Part 1 is behind us as last year’s special dividend payout of $4.34 per share, or $325 million total was returned to shareholders, as directed by activists. Going forward, the company says it currently has an additional $90 million or about $1.30 per share based on current outstanding share counts.

Also, the company maintains a target for return on equity (ROE) of 20%. Since buybacks are the quickest way to increase ROE, by reducing the denominator (shares outstanding) we concede these are probable so we add another 0.43 per share for annual buybacks ($150 million announced/5 years = $30 million divided by outstanding share count). These two events indicate approximately $1.73 per share for the next special dividend and possibly more depending on how aggressive management is to find sources. Even if we add another $1 per share from the graph above in the more uncertain (2-debt financing maneuvers 3-real estate options), that’s roughly $2.75 of shareholder value. This additional “value” in the form of a special dividend and associated activity adds incremental risk, and anything above this level really will stress the company’s resources especially if operations incur any type of hiccup. The liquidity analysis in the Capital Allocation and Financial Review indicates to us that all the new value from savings assumes no risk to the availability of the GE revolving credit facility and the smooth transition of intercompany lending between different segments.

Dropping the Hammer

It also seems logical that during an inevitable art market ‘correction’ if the art owners can’t find bids, they could short Sotheby’s stock themselves as a logical hedge. Famed short-seller Jim Chanos of Kynikos may be one such example. An art collector himself, Chanos has reportedly been short Sotheby’s. Chanos documents in a CNBC interview how Sotheby’s stock has peaked along with every major market top since at least 1987; see chart below.

BID’s share price usually peaks prior to the overall market, and shares have gotten clobbered disproportionately every time the overall market has. During the tech bubble, BID peaked in 1999 just preceding the overall market’s top (what market technicians call a “non-confirmation”), a sign of relative weakness. Given that BID’s share price dropped 87% during dotcom bust and 90% over the financial crisis, at a current price of $44.89 we want to avoid owning a stock exhibiting relative weakness in front of arguably the biggest bubble of all. What’s more concerning is that the actual art market itself, didn’t really flinch during the financial crisis, yet Sotheby’s stock still lost 90% of its value. It reveals that Sotheby’s is as much a financing and liquidity proxy as a player in the art market. As the art boom has frenzied higher still since the financial crisis, what happens to Sotheby’s stock price when the actual art market cracks?

While the ‘Old Masters’ (Picasso, Monet) are garnering the most eye-catching headlines and record sales prices, the category that’s really the art world’s, and Sotheby’s, current growth engine is Contemporary. The art market has seen a surge in works by modern or contemporary artists over recent years. The pieces (supply) of a contemporary artist are obviously not fixed since the artists are still alive. Maybe the ultimate indicator is the “insider selling” coming from the contemporary artists themselves. The contemporary style has garnered works totaling $271.4M, up from $175.3M, a year-over-year increase of 55%.

The art market itself seems to have several similarities to the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s. Art prices and sales are having what appears to be a blow-off top a la NASDAQ circa Q1 2000. Back then, the overall stock market was frothy, but it was the white-hot dotcom stocks and illiquid IPOs with floats sometimes as low as a few million shares. Note the similarities to today. The most insane prices for artworks are for the old classics since there is extremely limited supply. There are also several reports of artwork “flipping” (by presumed non-experts including notable film producers, celebrities and hedge fund managers). Flipping has always a necessary ingredient in bubbles (from tulip bulbs, dotcom stocks, pre-construction Miami condos, etc.) in line with the greater fool theory. The aforementioned contemporary artists, still living, are continually bringing new pieces to market like ‘Three Urinals,’ “Balloon dog” and even a dead shark in formaldehyde. I believe we will chuckle at these just like we chuckled about Pets.com, Theglobe.com or Webvan. Those dotcom classics are punch lines today, but I recall they were taken very seriously by many, just as these contemporary pieces are today…

So what’s Sotheby’s final sale price?

Our “base case” model sets a 12-month price target of $36.62. Our DCF methodology takes into account ‘moderate’ correction assumptions in terms of various equity market returns, interest rates and volatility and their effects on various pro forma estimates including somewhat optimistic assumptions for dividend payouts as inferred above.

Our “optimistic case” (worst case given our bearish stance) model sets a 12-month price target of $19. This DCF methodology takes into account ‘severe’ correction assumptions in terms of various equity market returns, liquidity issues, significant counterparty default risks, credit market disruptions, deflationary pressures, interest rates levels, volatility spikes and their effects on various pro forma estimates including pessimistic assumptions for dividend payouts as inferred above. We eventually (beyond 12-months) see Sotheby’s retesting the $6 per share level it visited in 2002 and 2009 at the lows of those crises. We guess beauty really is in the eye of the beholder.